Join Helga Zepp-LaRouche on Martin Luther King’s birthday, Monday, January 17 at 11am EST.

In reviewing the ongoing series of discussions this week between Russia, the U.S. and NATO — which she said so far “looks terrible” — Helga Zepp-LaRouche returned to what she described as the two alternative approaches to relations between nations. The Versailles Treaty at the end of World War I has in common with the posture of the U.S. and NATO today the view that the victors in war can dictate the terms of peace, as a unipolar force. This blatant assertion of world dominance ignores the legitimate wishes of other nations, and insists on their subordination to the unipolar power. This typifies the “arrogance of power” of today’s globalist war hawks, who claim the U.S. “won the Cold War”, and therefore has the right to be the dominant world power.

In contrast, the Peace of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years War in 1648, was based on the idea that recognizing the “interests of others” is the key to a durable peace. The outright rejection thus far by U.S. negotiators of the legitimacy of President Putin’s security concerns will not be accepted by Russia. While it is better to talk than not, she said, the overall posture of the U.S. in these talks has “lowered the nuclear threshold”, making the use of nuclear weapons more likely should war break out.

NATO, which should have been dissolved at the end of the Cold War, must be replaced, especially since its present policy course leads to a war in which its members in Europe will be destroyed. Belonging to a security alliance which would lead to war doesn’t make sense. Demonizing Putin and attacking the Belt-and-Road Initiative when the western financial system is crashing also does not make sense. She concluded by calling on our viewers to participate in the emergency Schiller Institute’s online seminar on January 17, on the theme, “Stop the Murder of Afghanistan.”

Has there been any progress in the ongoing talks between U.S. and Russian reps? The best that can be said is that it’s good they are talking, but statements issued by them show that the Russians have not received the agreement they are seeking, as the U.S. continues to insist it will not accept Russian “red lines” on NATO expansion and arms to Ukraine. Meanwhile, the attempt at a “Color Revolution” coup in Kazakhstan has been thwarted by decisive action by the CSTO allies of the nation. “Russia will not allow a ‘Color Revolution'”, Putin stated yesterday, after revealing that “Maidan technologies” — a reference to the methods used in the 2014 coup in Ukraine — had been employed in Kazakhstan.

HARLEY SCHLANGER: Hello, I’m Harley Schlanger with the Schiller Institute and Executive Intelligence Review. It’s January 6, 2022, and I’m joined today, very happily, by Dr. Andrey Kortunov, the director general of the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC). He’s been a participant at several Schiller Institute conferences. The RIAC itself is a very prestigious and important institute in shaping Russian foreign policy. We’re speaking at a moment of heightened tension between the U.S. and NATO with Russia, but also on the eve of a number of dialogues which have a potential for a breakthrough, and we want to explore this with Dr. Kortunov.

Andrey, thank you for joining us today.

ANDREY KORTUNOV: You’re welcome.

SCHLANGER: The tension that’s been growing in the most recent period can be traced back to the Dec. 3rd leak in the Washington Post, claiming that the Russians and President Putin are about to invade Ukraine. This has led to several discussions, two talks, in fact, videoconference talks between Presidents Putin and Biden. And there is a demand from President Putin that there be a discussion about legally binding agreements for Russian national security.

I’d like to start by just asking you, why do you think at this time, there’s been increased tensions? I don’t mean to say it just started Dec. 3rd, but we’ve seen a constant drumbeat since then.

KORTUNOV: Well, it’s hard to tell what exactly triggered the current escalation, but I think it was simmering for some time. If you look at the Russian side of the equation, of course, there has been a growing disappointment with the performance of the Normandy group, and I think that right now, there are very clear frustrations about the ability of this group to lead to the full implementation of the Minsk agreements. There were hopes when Mr. Zelenskyy came to power in Kiev, that he would be very different from his predecessor, Mr. Poroshenko, but at the end of the day, it turned out that it was more of the same. He introduced new legislation on languages, which implies naturalization of the use of the Russian language in Ukraine; he banned a couple of important and influential opposition media; and he prosecution some of Russia-friendly politicians in his country, so the perception was that probably we cannot expect too much from him.

Likewise, there was growing frustration with Paris and Berlin, in terms of their ability to use their leverage in Kiev to make the Ukrainian side implement the Minsk agreements. And an indicator of this was the publication of an exchange of letters between Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov and his peers in Paris and in Berlin, a very unorthodox, unusual step for Russian diplomacy, which suggests that Russia cannot really count on Berlin and Paris as honest brokers in this context.

So, I think ultimately, the decision was made that we should bring it to the attention to President Biden, because President Biden might be a tough negotiator, but he at least delivers on his commitments. And Biden has demonstrated that he is ready to continue a dialogue with Moscow. They had a meeting with President Putin in June of last year in Geneva, and I think that the decision was made that we should count on the United States more than on our European partners.

This is how I see the situation on the Russian side. And of course, there are also concerns about what Putin called a “military cultivation” of the Ukrainian territory by the North Atlantic Alliance. Looking at the situation from Moscow, one can see that although Ukraine is not a member to the NATO alliance, but there is more and more military cooperation between Ukraine and countries like the United States, and Germany, and the United Kingdom, and Turkey, and that changes the equation in the east of Ukraine; and I think that the concerns in Moscow are that at some point, President Zelenskyy, or whoever is in charge in Kiev, might decide to go for a military solution of the Donbas problem, and this is definitely not something that Moscow would like to see. So in certain ways, the Russian policy in Ukraine is that of deterrence, to deny Kiev a military solution for the problem of the east.

SCHLANGER: Now, you wrote that you don’t believe that President Putin intends to invade Ukraine: That it would be an enormous cost to Russia, and that, in fact, sending troops to the border which was within Russia, may be in all this increased tension, may be designed to send a signal to the West—you just mentioned France and Germany. But do you think the West is getting the signal? Annalena Baerbock, the German Foreign Minister, was just in Washington and she and Blinken were rattling their sabers, a little bit, again. Stoltenberg of NATO continues to make very strong statements. Do you think the signal is being recognized, or it’s reaching the people that need to understand what President Putin is insisting on?

KORTUNOV: Well, I think that it really depends on how you define “recognition” of the signal: Because on the one hand, indeed, you’re absolutely right, we observe a lot of rather militant rhetoric coming from the West, and it is not limited to Washington and to Berlin only. We see some other Western countries, where they make very strong statements, denying Russian veto power over decisions that are made, or can be made within the NATO alliance.

But on the other hand, you can also observe that there is a readiness, at least, to start talking to Moscow, and this is exactly what Mr. Putin apparently wants. His point is that if we do not generate a certain tension, you will not listen to us, you will not even hear us. So we are forced to make all these noises in order to get heard, if not listened to. So they are ready to meet. I am not too optimistic about potential breakthroughs that can be reached within these meetings, but the idea to meet and to discuss a band of issues is already something that President Putin can claim as his foreign policy accomplishment.

SCHLANGER: Now, in the United States, the media are continuing to paint President Putin as an autocrat, Russia as authoritarian nation, and they’re sort of missing one of the broader points here, which is that we’re looking at something which could be described as a reverse Cuban Missile Crisis. And I just went through President Kennedy’s Oct. 22, 1962, where he made a point very parallel to what President Putin is saying, which is that no nation can tolerate offensive weapons that close to its border, as the Soviet weapons were to the U.S. in Cuba. Do you think this is something that is part of the consideration from the standpoint of President Putin and the Russian government?

KORTUNOV: Well, I think that, again, you’re right, here. I think that definitely President Putin implies that there are certain rules of the game, maybe not codified rules of the game, that should be observed. And I think that when we’re talking about the U.S. position, there is a standard U.S. feeling of exclusiveness—we can do it because we are good guys, so we cannot harbor any evil intentions, so our missiles are fine. These are peacekeeping missiles, they cannot constitute any threat to Russia or to anyone else. But if you guys put your missiles in the vicinity of our borders, since you are bad guys, it means your missiles are also bad, and that they should be removed. Of course, the United States pursues this policy of double standards for a very long time, and I understand why the United States is doing that, but I think that such double standards can no longer work in our world. So, if we agree that there should be some constraints, and that security interests of major powers should be taken into consideration, then it should be applied universally. It should not be applied to the United States only, but it should be applied to Russia, to China, to some other countries as well.

SCHLANGER: Now, you’ve spoken of your view that there needs to be a new security architecture, to replace the existing bloc structure which seems to be left over from the Cold War. Just a few days ago, the permanent five nations of the UN Security Council issued a statement, which I think was quite extraordinary, that “nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,” which is an echo of the discussion between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev back in October 1986 in Reykjavik. Is this the kind of thing that can move toward a new security architecture, or recognition of something like this? And what kind of changes would you like to see, in order to create stability and ease the tensions?

KORTUNOV: Well, I would say that this is an important first step, and the question is whether this step will have any continuation. Because it is relatively easy, though it is difficult in itself, but it is, in relative terms, it is easier to make a general statement, without making any specific commitments, than to go for something more practical. I guess that one of the problems we see in Europe, in particular, is that NATO has monopolized the security agenda in Europe, and that implies that if you are not within NATO, you have no stakes in the European security: You are not a stakeholder. And if you’re not a stakeholder, you are tempted to become a spoiler. And that is something that I see as a major problem.

So, in my view, the key goal should be not to reverse the NATO enlargement, which is not possible, I think. But rather to deprive NATO of its monopoly position on European security matters. That might imply giving more power and more authority more inclusive European institutions, like the Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), for example, which really needs some addition flesh on its bones. It has to be empowered, it has to become a real European multilateral organization that can take a part of the security agenda. There might be some other agreements, and some other arrangements that would diversify our security portfolio in Europe. But I think that definitely, any European system which excludes Russia by definition, is likely to be very—not very stable, let me put it in this way, and fragile, and it will have high maintenance costs. So, I think it’s better to have Russia in, rather than to have Russia out.

SCHLANGER: Now, in an article you wrote recently, “A Non-Alarmist Forecast for 2022,” one of the things you talked about is finding areas of cooperation. And you say one of the most urgent of these is Afghanistan for obvious reasons: the refugee crisis, the potential for radicalization of people if the humanitarian crisis deepens—as it is; David Beasley of the World Food Program just said yesterday, almost 9 million Afghans are at the verge of starvation. [https://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/a-non-alarmist-forecast-for-2022/]

Do you see a potential, then, through the Extended Troika—China, Pakistan, Russia, United States—to do something? And as you know, Mrs. Helga Zepp-LaRouche of the Schiller Institute has called for an “Operation Ibn Sina” to use the healthcare situation as the basis for beginning, not just emergency aid, but building up a modern healthcare system in Afghanistan. Is this some area, where you could see some cooperation?

KORTUNOV: Well, Afghanistan strikes me as one of a very few places in the world, where I see no major contradictions between the East and the West, between Russia and China on the one hand, and the United States and the European Union on the other. I think that everybody around Afghanistan, and also if we consider overseas powers, everybody is interested in seeing Afghanistan as a stable place, as a place which will not harbor international terrorism, as a place which will stop being a major drug producer and drug exporter to neighboring countries: So these interests are essentially the same. I would definitely call for an as broad international coalition to deal with Afghanistan as possible; and this coalition should involve not only neighboring countries—which are clearly very important—but also countries which have the stakes in Afghanistan. We can talk about the European Union which remains the largest assistance provider to Afghanistan, even today; we can talk about the United States with its residential influence in Afghanistan; we can talk about Pakistan, Turkey, Iran, and the Central Asian states.

So I think the broader the coalition we have in dealing with Afghanistan the better it is, because it would mean that we have more leverage in dealing with the regime in Kabul and that also implies that we can agree on the red lines that this regime should not cross if it wants to maintain its international legitimacy.

So I think Afghanistan can be regarded not only as a challenge, but also as an opportunity for a multilateral, international cooperation. We can talk about the Extended Troika. We can talk about the SCO [Shanghai Cooperation Organization] as a platform to discuss Afghanistan. We can talk about other formats, but formats are just tools in our hands. The key issue is to agree on what we expect from the Taliban, and what we can give the Taliban in exchange.

SCHLANGER: Now, another area I want to take up with you is the Russia-China alliance. This is causing sleepless nights for a lot of the geopoliticians who see this as primarily a military alliance and it seems as though they’re ignoring the economic benefits of Eurasian integration, including potential benefits for the West. I wonder what your thoughts are on this? Is this going to continue the alliance, and is it more than just a reaction to the targetting of Moscow and Beijing by the Western war-hawks?

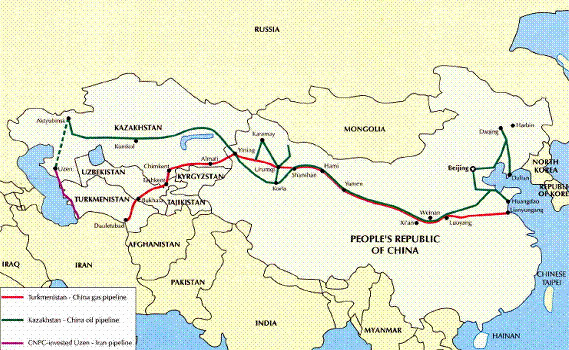

KORTUNOV: I think that these days, everybody is pivoted to Asia, Asia is becoming an important driver of the global economic development, and you cannot ignore China, no matter where you sit—whether you sit in Moscow, or Brussels, or in Washington, you have to keep in mind what’s going on in Beijing. So the Russian-Chinese cooperation has its own logic: We have arguably the longest land border in the world, and definitely, there is a natural complementarity of the Russian and the Chinese economies. Trade is growing pretty fast: I think if you take last year, it was about $140 billion and there is a lot of potential there. There are also common interests: there are interests that the two countries share in terms of Eurasia, and we discussed Afghanistan; definitely this is where Russian and Chinese interests mostly coincide. We can talk about the situation in Northeast Asia, and again, here, there is a noble effort for Russian and Chinese interests.

As far as the United States is concerned, I think definitely both countries are exposed to political and military and economic pressures from Washington. The Biden administration continues the policy of dual containment targetted as both Beijing and Moscow, and that is an additional factor that brings Russia and China closer to each other.

But let me emphasize once again that the Russian-Chinese cooperation has its own dynamics, its own logic and this logic does not depend fully on the position of the United States though this position is important for politicians both in Russia and in China.

SCHLANGER: I want to come back to the P5 statement on not fighting nuclear wars, because we’ve raised this before in discussion with you: President Putin in January of 2020 proposed a P5 summit, so that it’s broader than just the United States and Russia. Do you still see this as a venue that would be an appropriate one for taking up some of these broader issues?

KORTUNOV: I think it would be important, at least, in order to reactivate the United Nations Security Council. Because unfortunately, we see on many important issues, the council cannot really deliver, because there are very clear disagreements between its permanent members and that prevents the council from taking a consolidated action. So I think if they discuss some of the regional issues at such a meeting; if they discuss issues like nonproliferation, or the fight against international terrorism, or let’s say, energy or food security, that would be helpful. Of course, the P5 cannot decide on every single international issue. They cannot resolve all the global problems without participation of other states, but you have to start somewhere, and maybe a P5 meeting, face to face hopefully, will be this important starting point. If it is successful, then we can complement it with other formats, for example, when we talk about the economic dimension we can do a lot within the G20 framework, and that should complement the efforts of the Security Council. Some issues can be discussed in the framework of bilateral U.S.-Russian negotiations, some of them will require multilateral discussions, in multilateral formats.

So formats might be different. The question is whether they have the political will to pursue this agenda, whether they are ready to go beyond their conventional wisdom and think strategically.

SCHLANGER: And on this question then of bilateral discussion, do you think there’s a prospect for progress on nuclear arms discussions in the year ahead?

KORTUNOV: I think that if there is a will, there is a way, of course. But it will be an uphill battle for both sides, because it’s not clear what we could have after the New START agreement expires in about four years from now. The arms race is changing. It’s no longer about numbers, it’s no longer about warheads and delivery means. It’s about quantity, it’s about precision, it’s about prompt strike, it’s about autonomous lethal weapons, it’s about cyborgs, it’s about space, and we still have to find ways to counter these very dangerous, destabilizing trends in the nuclear arms race. On top of that, we have a very serious problem of how to multilateralize strategic arms control, because the lower we go—I mean “we,” the United States and Russian Federation—the lower we go, the more important nuclear capacities of a third country become, and we have to engage them in this way or another into the arms control of the future.

So there are many issues here. I will say I’m probably pessimistic about the future of arms control, but it will require a lot of commitment, a lot of patience and a lot of stamina.

SCHLANGER: Somewhat pressing right now, which is the situation in Kazakhstan: We were talking last night, given the upcoming meetings and the potential for a breakthrough, that maybe we should be watching for something coming out of the blue that could be a destabilizing influence. And there are elements of what’s happening in Kazakhstan which are coherent with what we’ve seen with color revolutions in the past, including Western intervention into the affairs of other countries. Do you have any reading on this? Any thoughts on that?

KORTUNOV: Well, it’s hard to tell. It’s probably too early to jump to conclusions, because of course, there will be people in the West who would applaud the kind of developments in Kazakhstan. At the same time, for instance, if you look at large American oil and mining companies, they had a pretty good business in Kazakhstan, and they cannot be interested in a political destabilization there. So I’m not sure that the United States has been directly involved in staging a color revolution in Kazakhstan. But definitely, there are some external players, that might be interested in turmoil and mutiny in Kazakhstan. Having said that, I should underscore that there are some fundamental domestic roots of the problem: Definitely the leadership of the country was too slow to react to the social and economics demands of the population. They promised political reforms, but again, they dragged their feet on this issue, which triggered the events that we now observe.

I can only hope that everybody will learn appropriate lessons. The state authorities should learn how important it is to keep an eye on the changing moods of society, and protesters should also learn that the borderline between peaceful protests and violent extremism might be murky. We now see that already hundreds of people, unfortunately, were killed in Kazakhstan. There were many cases of looting and vandalism, and definitely this is something that has to be stopped.

SCHLANGER: Well, Andrey, thank you very much for your time and joining us today.

KORTUNOV: Thank you.

SCHLANGER: As these meetings take place and we see new developments, I’d like to be able to have an opportunity to speak with you again and see how these things are moving.

KORTUNOV: My pleasure, thank you.

In reviewing events of the last days, Helga Zepp-LaRouche raised the question of whether the violent demonstrations that broke out yesterday in Kazakhstan were designed to disrupt the potential progress between the U.S. and Russia which could result from a series of upcoming diplomatic events. It’s too early to tell if this is an organized “Color Revolution”, she said, but should be investigated, as it is clear the riots in several cities were coordinated. She said she had been expecting a provocation to disrupt the meetings, which begin with a U.S.-Russian Strategic Stability dialogue meeting on January 10. With the announcement by the P5 of the U.N. Security Council that nuclear wars cannot be won, and must not be fought, there is a possibility for a breakthrough away from the geopolitical provocations and tension, which has been building.

There are still obstacles to progress, typified by the Baerbock-Blinken talks, in which the German Foreign Minister proved again that she is a loud-speaker for NATO in provocations against Russia and China. It is also shameful that there is still no action to relieve the humanitarian debacle unfolding in Afghanistan. Our role with Operation Ibn Sina is essential to awaken people out of the moral indifference which characterizes the actions of all governments, which do not act for the Common Good.

Col. Richard Black: U.S. Leading World to Nuclear War

Read the full transcript here.

The Illegal Balkan Wars and the Ukraine Parallel — Interview with Nebojša Malić

Read the full transcript here.

Interview with Joel Dejean — LaRouche Independent Candidate for Congress

Read the full transcript here.

LaRouche Candidate Diane Sare vs. Sen. Chuck Schumer: Make NY the Ctr of Peace Through Development

Read the full transcript here.

Global Britain: An Archaic Project That May Bring Global Nuclear War

Read the full transcript here.

Cooperate with China – It Is Not the Enemy

Read the full transcript here.

Only A Systemic Change Can Save the U.S.

Read the full transcript here.

Ray McGovern: Putin is Being Heard on U.S.-Russia Policy

Full transcript available here.

Will the U.S.-Russian Strategic Dialogue Be a Step Back from War? Interview with Andrey Kortunov

Full transcript available here.

U.S. Confrontation With China Is Destroying the U.S. — Interview with Dr. George Koo

Full transcript is available here.

Interview with Russia expert Jens Jørgen Nielsen—How to avoid war between the U.S./NATO and Russia?

Full transcript is available here.

EIR Interview with Justin Lin: China and Hamiltonian Economics

Full transcript is available here.

U.S. Policy Is ‘Suffocating the Afghan People’ — Interview with Dr. Shah Mehrabi

Full transcript is available here.

Graham Fuller: End U.S. Addiction to Never Ending War

Full transcript is available here.

Jan Oberg, PhD, peace and future researcher:

Full transcript available here.

Dr. Li Xing The China Russia Feb 4 Joint Statement A Declaration of a New Era and New World Order

Full transcript available here.

EIR Interview with former US Ambassador and China expert Chas Freeman

The following is an edited transcription of an interview conducted with Dr. George Koo, by Michael Billington on December 29, 2021. Dr. Koo is one of the leading Chinese-American writers and organizers in regard to U.S.-China policy and on the conditions of Chinese-Americans in the United States, especially the persecution over these last years of Chinese-Americans and Chinese in the U.S. Subheads, embedded links, and footnotes have been added.

EIR: This is Mike Billington with the Executive Intelligence Review, the Schiller Institute, and the LaRouche Organization. I’m here with Dr. George Koo.

Would you like to say a few words about your own history, Dr. Koo, when you came to the U.S., your education and your career?

Dr. Koo: Thank you. And Mike, thank you for inviting me. It’s a pleasure to be with you. I started a draft of my autobiography, and my working title is Best of Both Worlds. By that, I mean, of my first 11 years in China, which was in, probably, one of the worst periods of Chinese history—war torn China—I was fortunate. I never saw a single Japanese soldier, and I never lived under the Japanese occupation with all its brutality and inhumanity.

What happened was, my parents graduated from, and were affiliated with, Xiamen University. The leaders of that university, in their wisdom, knew that the Xiamen Harbor was too strategic to be {not} occupied by the Japanese troops. So in 1937, they picked up and moved roughly 200 miles into the interior part of Fujian province. China is very mountainous, so 200 miles is actually quite an appreciable distance away from Xiamen, and as a consequence, the Japanese never saw the strategic need to occupy the area, a very small hamlet called Changting. I was born there, and because of that, I actually had a very nurturing, peaceful upbringing by my parents.

I was actually a couple of years ahead of my class in the grammar school. When the war was over and we moved back to Xiamen, I went back a year, because all my fellow students were five years older than I was, because they were interrupted by the war.

When I came to the U.S., I had graduated from sixth grade, which gave me a nice foundation—not only the Chinese language, but also an appreciation of the Chinese culture and Chinese history. I was fortunate. My father had already gotten a fellowship from the nationalist government. They used some of the war reparations from Japan to send some of their students to continue their graduate education after World War Two, and my father was among them. He was in Seattle already, continuing his graduate studies. He was trained as a marine biologist, and was in the University of Washington to study fisheries.

In 1949, a lot of these divided families—where the scholar was in the U.S. for further education but the family stayed behind on the mainland—they all had to make a crucial decision, whether they were going to leave the U.S. and go back to China, or they were going to try to get their families to come to the U.S., or they would face an uncertain period of separation. We were fortunate—we were able to emigrate to the U.S. in 1949. I was eleven at the time, didn’t know a word of English, but the Seattle public school system was really, really outstanding. We didn’t feel that we had to go to a private school, so I was brought up through the Seattle public schools. I caught up with my English by the time I graduated from high school.

I was fortunate enough to get a partial scholarship and work program to attend MIT. I went to MIT for my bachelor’s and master’s degrees. I got married—my wife was similarly a Chinese-American who came to the U.S. when she was, I think, six years old. We met at MIT in graduate school. I joined Boeing, worked at Boeing on their Saturn project, and subsequently joined Allied Chemical, continuing my graduate studies, and got my doctorate degree at Stevens Institute of Technology. That’s pretty much the early part of my career.

I joined SRI [formerly the Stanford Research Institute] in conducting what is called industrial economic research. From there, I joined Chase Bank and subsequently Bear Stearns to work on China Trade Advisory Business. For an appreciable period of time, I was helping American businesses doing business in China, establishing business relationships and also negotiating joint venture contracts, cooperation, and so on. From that basis, I developed a very basic understanding of China, how China works, where they’re coming from. As we got later into the relationship, I could see that there was a tremendous gap in understanding between China and the U.S., and I sort of took upon myself the role to help bridge the understanding between the two countries. That’s when I began to write about U.S.-China relations. This is, I guess, what we’ll talk about today.

Confrontation Is Lose-Lose

EIR: A lot of that I didn’t know. I’m glad to learn that about you. You spoke at the Schiller Institute conference on November 13. Your presentation was called “The Survival of Our World Depends on Whether the U.S. and China Can Get Along.” You noted there that the Chinese economy, by certain kinds of accounting, is now larger than that of the U.S., and that the U.S. response has been, as you said, to “push China’s head underwater rather than trying to compete on its own.” I concur with you on that. What would you say is the economic and technological impact of that policy, both on China, and also on the U.S.?

Dr.Koo: It’s unfortunately a zero-sum approach that the U.S. is taking

First, it assumes that by taking this approach the U.S. will win at the expense of China, and that China will lose. But what will actually happen, of course, in a zero-sum approach, is that each side will try to endeavor to win at the expense of the other. The eventual outcome is lose-lose—both sides lose. It’s arguable whether China will lose more than the U.S., and the reason I say that is because, China has a much more vibrant, healthy trading relationship with virtually all parts of the world compared to the U.S. So, economically, they have a lot more reach and flexibility.

Second, it goes without saying that China has a very complete, robust manufacturing base, which we do not. We have already emptied out our manufacturing base, and for Trump to impose a tariff barrier and presume that that will bring the manufacturing base back is very wrongheaded. It shows his, I guess, ignorance on the basic principles of economics. I don’t find, and I don’t expect, that very many manufacturing firms will come back unless the economics is basically favorable. And as you know, the justification for the tariff barriers was that it was going to be “free money” coming to the U.S. Treasury, and the Chinese exporters were going to pay for it.

And of course, that was far from reality. The reality is the increased prices the American consumers end up paying, so it’s not free money; it’s coming out of one pocket and going to the other. That just raises the cost of living. There’s no question that by separating or attempting to separate the two economic spheres of influence, if you will, that both will lose. I’m not at all sure that the U.S. will come out ahead in a lose-lose outcome.

Ambassador Burlingame

EIR: You are also the head of something called the Burlingame Foundation, which is named after Anson Burlingame, the American diplomat in China who actually ended up representing China. Could you discuss a bit about his career, when there was an attempt by the U.S. to establish good relations with China, which was at that time under the boot of the British?

Dr. Koo: About 13 years ago I happened to catch, in a very small local newspaper that covers the city of Burlingame, that the Burlingame Historical Society wrote about the life of Anson Burlingame—that’s the first time I heard about him, and that the city of Burlingame was named after him. So I read up on it. I was fascinated because, here is somebody who was a dedicated abolitionist, anti-slavery, who placed the highest importance on human rights and human dignity, and was one of the founders of the Republican Party and an energetic, vigorous supporter of Abraham Lincoln, and helped get Lincoln elected. He worked so hard that he lost his own re-election as a congressman from Massachusetts.

So, Lincoln offered to appoint him as an ambassador, first to the Austria-Hungary Empire. But the Austrian government didn’t want Burlingame—Burlingame was very vocal about the suppression of the Hungarians by the Austrian emperor, so he was persona non grata from the get-go. So then Lincoln appointed him to be ambassador to China. He left the U.S. in 1861, but he took his time, landed in Hong Kong, and travelled up through China gradually so that he could learn more about the Chinese culture, the Chinese people, the Chinese history. By the time he got to Beijing, it was already 1862.

He made his stand very clear: that China’s sovereignty was to be respected, that he was not there to carve up China for the U.S., unlike the British and other Western powers that were based there. He was very outspoken on what was fair in how to deal with China from a U.S. point of view. In fact, when some American was accused of murdering some Chinese nationals while he was Ambassador, he had him arrested, presided over his trial, and accepted witnesses from China—Chinese witnesses, which was unheard of if you were a British court or a French court or some of the others. He then pronounced him guilty and sentenced him to be executed. (I think he never got executed, because he escaped, but that’s a different story.)

All of that very much impressed the regent behind the throne. His name was Prince Gong, Gong Qing Wang in Chinese. Prince Gong was so impressed with Anson Burlingame and his integrity that when Burlingame was all set to return to the U.S.—that would have been 1867—Prince Gong went to see him and said, “Mr. Burlingame, we need to go to the Western countries and try to renegotiate the various unequal treaties that have been imposed upon us. We have a team all set to go, but we need someone of international stature to lead this group. Would you be willing to lead it?” Burlingame immediately accepted the appointment, wrote a letter to his boss, the Secretary of State, William Seward, and said, “Hey, I’m coming back, but I’m coming back as an Ambassador from China,” and that’s what happened.

He came to the U.S. in early 1868, took the train that the Chinese had helped to build, the Transcontinental Railroad, celebrated all along the way, got to Washington, and negotiated a treaty called—in shorthand—the Burlingame Treaty of 1868. That treaty recognizes the mutual sovereignty, the equal rights of citizens from one country living in the other, the mutual rights to emigrate from one to the other. It was the first treaty that China enjoyed with the Western countries of that kind, and that set a different relationship between the U.S. and China that had lasting effects, even though the Chinese exclusion laws of 1882 canceled the Burlingame Treaty.

One of the lasting effects was the Chinese Educational Mission that was organized, I think, starting in 1871. This mission was organized by a guy by the name of Rong Hong, or in Cantonese, Yung Wing. He had been brought over [to the U.S.] earlier by American missionaries, and was a graduate of Yale. When he went back to China, he was entrusted by the Manchu government to be the intermediary between the U.S. and China. He brought a munitions plant—a turnkey plant—from the U.S. to China, and convinced one of the senior officials there that China should send young boys somewhat like himself to the U.S. to get a U.S. education. Through a lot of effort on his part, he convinced families, mostly families in the Guangzhou area, to send 120 boys to the U.S. to be educated. Thirty boys a year were sent over a four-year period.

The first batch landed in 1871. They were all 12, 13 years old, if you can imagine.

They ended up in Connecticut, in New England; they were being hosted mostly by Christian families in their area and educated in American schools. Some of them became old enough to attend college, such as MIT, Yale—a lot of them went to Yale because of Rong Hong—and Columbia—and some others of the best schools on the East Coast.

It only lasted four years. The third- and fourth-year batches of young kids never got to finish or attend college, because the internal politics of China became very negative, watching these young Chinese kids becoming “too Americanized,” and losing their Chinese roots and Chinese culture. So, they brought them back and interrupted their education. Nevertheless, this group of Western-educated young Chinese later on went on to have a tremendous influence, especially after the fall of the Manchu dynasty and in the Republican government.

One of them, who was actually an outstanding baseball pitcher and hitter when he was in the U.S., was appointed Ambassador to Washington. He got to be good friends with Teddy Roosevelt — he was the one who convinced Roosevelt, by the time he got to be President, that the indemnity funds which the Chinese were paying to the U.S.1The foreign powers whose missions were attacked in the so-called Boxer Rebellion (1888-1901) punished China by, among things, imposing reparations payments of $330 million—the “Boxer Indemnity.” could be better used by sending them back to train and educate Chinese in the American system of education.

Some of that money funded the building of Tsinghua University that we now know in Beijing, and also funded some of the outstanding students from China to be educated in the U.S.2In 1908 the U.S. Congress passed a bill to return to China $17 million, its share of the remaining Boxer Indemnity. President Theodore Roosevelt’s administration then established the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program to educate Chinese students in the U.S., starting in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s, including my father-in-law, by the way. He was sent to get a bachelor’s degree from MIT, a master’s from Pennsylvania, and a doctorate in electrical engineering from Harvard. Boeing’ chief engineer, Wong Tsu, was one of that batch. He went to Boeing, designed the first sea plane, which the U.S. Navy bought, and that got Boeing started. Then Wong Tsu went back to China. There’s a whole list of people which that particular mission created.

Now back to Burlingame. After he successfully negotiated the Burlingame Treaty of 1868, he then took the Chinese delegation and went to Europe. He visited the British, the French, and others, trying to convince them that they should do the same. Of course, none of those countries were interested in recognizing China on an equal sovereignty basis. But they also didn’t want to antagonize somebody of Burlingame’s stature. So, they just sort of fobbed him off and stalled. Eventually he ended up in St. Petersburg in February of 1870. There he contracted pneumonia and died within four days. He was a few days short of his 50th birthday when he died in the service of China.

This story, by the way, is pretty much forgotten in the U.S. especially, but also in China. But one of the young reporters that he befriended on his way to China was a beginning reporter by the name Sam Clemens, who later on, as you know, became Mark Twain. And Mark Twain wrote probably the best eulogy on Anson Burlingame when Burlingame died.

So the reason for me and some of the others to start the Burlingame Foundation was really to remind the people of the world, especially in the U.S. and China, that there was a point in time in history when the relationship between the two countries was really exemplary, and we would like to see it go back to that basis again.

Sun Yat-sen and the American System

EIR: Yes, indeed. As you know, Dr. Sun Yat-sen was not educated in the United States, exactly, but he and his brother went from the Guangzhou area to Hawaii to work, where he was taken under the care of a missionary family who were part of the Henry Carey School, who had studied the American System of economics developed by Alexander Hamilton.

When Sun Yat-sen then came back to China and ended up organizing the Republican movement that led to the overthrow of the dynasty in 1911 and the establishment of the Chinese Republic, his organizing was based on what he called the Three Principles of the People, which was based on the ideas of Abraham Lincoln, who said “government of the people, by the people and for the people.” In particular, Dr. Sun understood and taught the American System as it was invented by Alexander Hamilton. He even understood the factional differences within the United States, that Thomas Jefferson, although he wanted independence, was a follower of the British laissez faire system, including slavery, and so forth.

This was Sun Yat-sen’s legacy. But that, too, is generally unknown in the United States. So, I’m wondering what you think about the impact of Sun Yat-sen in China and in the United States, how that is impacting things today, because it’s clear that the Chinese economists who are leading the miracle in China today are very, very familiar with this tradition.

Dr. Koo: Yes, I think it’s fair to say that the influence of Sun Yat-sen, or in Chinese, Sun Zhongshan, continues to be a legacy that is still admired and studied, even in today’s China, even though he was not a leader of the Communist Party movement. However, while he was alive—and unfortunately, he didn’t live very long after the revolution—he wanted to accommodate both the Kuomintang (the Nationalist Party), and the Communist Party, and wanted them to work together, which was not to be, as we know. No question that his Three Principles is taken directly from Abraham Lincoln; he was an unabashed admirer of the American System and democracy as defined by the U.S.

To a large extent, I think, as you said, the Communist Party, since the founding of the PRC [People’s Republic of China] very much did follow Sun Yat-sen’s doctrine along the way. One of Hamilton’s principles was the protection of homegrown industries through tariff barriers, and we saw China do that. They did protect their homegrown industries—they called them the pillar industries. They would protect them from competition, up to a certain point. But they also understand that there is an endpoint to when protective barriers, tariff barriers, cease to be working in their own interests.

A lot of other emerging countries don’t understand that. Once they set up the tariff barriers, they don’t seem to have the ability or the wherewithal to remove these barriers, and the long-term consequences of having tariff barriers forever is to keep your own homegrown industries protected, but never competitive, because they’re not able to compete in the open trade situation. Now, we know that China has surpassed that handicap, because once they joined the WTO, and Premier Zhu Rongji started to remove the protection, it’s a sink or swim situation for the Chinese companies. Those that didn’t make it, that sank, were absorbed in the Chinese economy. Fortunately, I think the Chinese economy grew fast enough to take up the slack of the under- or unemployed as a result of having to face world competition.

War Over Taiwan?

EIR: Let me address the strategic crisis that we’re living through now between the U.S. and China. Ambassador Chas Freeman, who was the interpreter for Richard Nixon on his famous 1972 visit to China and who went on to have an esteemed diplomatic career, is a China scholar and expert. In an interview with EIR last month, said he thought that the U.S. had gone beyond the “red line” of China vis-à-vis the Taiwan situation, beyond the “One China, Two Systems” policy, by backing up the Democratic Progressive Party’s [DPP] policies in Taiwan, calling for independence. The U.S. appears to be sleepwalking into war both in the Russian and the Chinese situations, which could be, of course, disastrous for mankind.

Dr. Koo: Right.

EIR: You’re very familiar and knowledgeable about the developments in Taiwan. What do you think about how Taiwan got to the point that they’re now being used as a lever for a very evil policy?

Dr. Koo: Unfortunately, the party in power in Taiwan, the DPP, probably doesn’t see the situation the way you just enunciated. I think they’d like to see themselves as a tail trying to wag the dog.

Unfortunately, the Biden administration, like the Trump administration preceding it, is encouraging them on that line of thinking. By that, I mean, they are encouraged to push the line in the sand, if you will. I think we’ll have to go back to when the DPP came to power, with Chen Shui-bian their first elected President.3Chen Shui-bian served as President of Taiwan from 2000 to 2008. He was the first President from the Democratic Progressive Party which ended the Kuomintang’s 55 years of continuous rule in Taiwan.

It’s a very strange politics in Taiwan. Chen Shui-bian was elected because there was a bullet that made a right turn and grazed his belly on the night before the election, and also hit his vice president candidate in the knee. It created such an uproar that he successfully got enough sympathy votes to put him over and got him elected. Once he was elected, he changed the core [school] curriculum for grades K-12 and disconnected the Taiwan history from that of the mainland, so that the Taiwan kids growing up no longer know that they’re a part of the Chinese culture, Chinese history, and that their characters and poems and literature came originally from China.

So the disenchantment, or this disaffection, of the Taiwan people started with Chen Shui-bian, or perhaps even from Lee Teng-hui, when Lee Teng-hui was President.4 Lee Teng-hui served as President of Taiwan from 1988-2000. He was the Chairman of the Kuomintang during the same period. Gradually, the people in Taiwan have become more and more detached from any sense of affiliation with the mainland. That’s a very important factor that’s happening here. The other thing is that the DPP has very successfully convinced the people of Taiwan that they are infinitely better off than what’s going on in mainland China, despite the fact that, if they were fortunate enough to go to Shanghai and go to other places, they could see for themselves what a difference it is.

In fact, the elites, the better educated, better motivated, which is maybe a couple of million of the young Taiwanese people, are living and working in mainland China, establishing their careers there. A lot of them are working for Taiwan companies that are based in mainland China. They know the difference, but when they go back to Taiwan on home leave, they can’t even talk about it, because the local Taiwan folks would hoot at them and heckle them, and don’t believe what they’re saying.

So there’s a dichotomy here between Taiwan and mainland China. Beijing feels that time is on their side. Eventually, the people in Taiwan will recognize that it’s in their benefit to be part of China and not to be trying to be the fifty-first state of the United States of America, which will never happen, even though the DPP seems to be deluded in that sense and that feeling.

Is Taiwan a spark? I think Taiwan could be a spark for a war and conflagration if that’s what the United States wants. If the U.S. pushes to the point where Beijing feels that they have to respond, then we will have a disaster in our hands. But as you know, the way the situations are being portrayed by our mainstream media and by our politicians is totally distorted. Whether it’s about Taiwan, about Xinjiang, about Afghanistan, about any part of the world where we have troops and we have bases. Somehow, we’re there to save the world and the Chinese and the Russians are there to destroy the world. Whereas in actual fact, it’s just the opposite.

U.S. Destabilization in Hong Kong

EIR: You mentioned Hong Kong. I know you’ve been very active in business, as well as just knowledgeable about Hong Kong for a long time. As you know, in 2020, just as there were rioters in the streets across the United States burning down shops, shopping centers, attacking police and so on, the same thing had been going on in Hong Kong the year before, where masked, black-clad young people were driven to go out and set fires and attack police and so on. And yet this was called, in the U.S. press, in regard to he Hong Kong riots, “peaceful protests for democracy.” So, what is your view of the role of Hong Kong today in regard to China, as well as in its relations with the West?

Dr. Koo: I’m glad you brought it up, Mike, because this is a classic example, a fabrication and distortion, of what’s going on in Hong Kong. The riots in Hong Kong started in 2019. It all started because a young Hong Kong couple went to Taiwan and the boyfriend murdered the girlfriend, who was pregnant at the time, and cut up her body and put it in a suitcase, and then went back to Hong Kong by himself. And because there were no extradition treaties between Taiwan and Hong Kong, he basically went home scot-free and was free to roam around the streets. The law enforcement couldn’t do anything about it. So, that brought home the point and the need to have an extradition treaty between Hong Kong and rest of the world.

In fact, at the time, Hong Kong was one of the few territories or countries that did not have extradition treaties, neither with Taiwan nor with Beijing. So when the Chief Executive of Hong Kong started to enact an extradition treaty, the opposition, the “democracy movers” of Hong Kong, objected, created a riot, and insisted that they must not have this extradition treaty, because, they claimed, that with it they could be extradited, they could be arrested and be sent to Beijing at any time, and they would be threatened.

That really created the unrest and the riot. What we found out afterwards, is that those protesters were being funded by the NED, the National Endowment for Democracy, which is a CIA-funded arm whose mission is to create unrest, instability, and disturbance anywhere in the world, in countries where the power that reigns is not to our liking. That’s what happened in Hong Kong. The media not only considered it a democracy movement—one of our leaders, the Speaker of the House, as a matter of fact, publicly said, “What a beautiful sight that was!” Well, when the riots happened in the United States, I didn’t find anybody saying that they were a beautiful sight. It was clearly destruction and lawlessness and so on.

So today what we have in Hong Kong, we now have an extradition treaty in place, we have a pledge of allegiance to the Beijing government in place, and we have a voter turnout to elect a batch of legislators for the Hong Kong government. All three things are cause for the Western media to criticize and say this is lack of democracy in Hong Kong. Well, let’s look at it, OK? The voter turnout was very low, was 30%, to elect the legislators. This just happened.

Well, guess what? The normal turnout in New York City is 26%. So, do we say New York City is lacking democracy? Well, maybe it does lack democracy, but certainly you won’t find mainstream media reporting it on that basis. The Pledge of Allegiance? Well, it seems to me, we, in school, pledge allegiance to the flag all the time, and nobody complains about it as being an illegal maneuver. So, we’re looking at double standards, and it’s always to the benefit of us looking good and China looking bad.

Pompeo and BBC Lies About the Uyghurs

EIR: Perhaps the most extreme example of that was when Mike Pompeo began saying that China was guilty of genocide in Xinjiang against the Muslim Uyghur people, while anybody who would travel to Xinjiang would know how absurd that is. But nonetheless, it’s repeated in every newspaper, in the Congress, and in the White House. What can you tell us about the actual economic and social conditions of the Uyghur population in Xinjiang?

Dr. Koo: There is a purpose to Mike Pompeo and his successor, [Antony] Blinken, and the media coverage to emphasize, “human rights violations in Xinjiang,” to the point that now Biden is actually forbidding Americans from buying cotton from Xinjiang. What is the purpose? Well, the purpose is to keep the Uyghurs in Xinjiang poor and underemployed. And why do we do that? Because wherever there’s instability, that’s what we want. That’s how we, the United States, maintain control. We thrive on instability anywhere else in the world.

I’ll give you an example of a distortion. CGTN, which is the China Global Television Network, had a documentary that covered why China had recruited young Uyghur women to go to work in factories and in cities in other provinces. The idea of employment is income for her, skills for her to make a decent living, raise her living standard to the point that she could even afford to get her parents to move from Xinjiang for a better living. Uyghur women in Xinjiang do not get the proper education, they tend to stay home, marry young, have kids, and never have a chance to improve their living standard.

The documentary also showed that the first time that she had to leave home to go to a faraway city in China, she was crying, because this was the first time that she was going to leave home. Well, BBC took that documentary and skillfully cut and pasted so that it comes out with the message: “See? Beijing is exploiting slave labor again, forcing these young women to leave home to work for peon wages somewhere else.”

The same goes with picking cotton in Xinjiang: “Look at all these poor women picking cotton in Xinjiang.” Well, actually most of the cotton nowadays in Xinjiang is done by machines, and the machines are sold by John Deere, a very well-known American company. There’s so much fabrication and distortion going on. Mike Pompeo was actually very open compared to Blinken. Mike Pompeo said: “We lie, we cheat, we steal”—came right out in the open. Blinken does the same thing, but he’s a little smoother, so he doesn’t say, “We lie, we cheat, we steal.” But that’s what he does. He talks about, “China needs to follow the rules-based international order.” What is the rules-based international order?

Well, if you listen to Blinken, it turns out the “rules-based international order” is whatever he says it is, not by the United Nations or by a multipolar type of definition. And of course, he has continued to parrot the Xinjiang human rights violations.

I don’t know if you’re familiar with this guy by the name of Adrian Zenz, a German right-wing nut who’s been to Xinjiang maybe once, many years ago, and continues to spout all this fabrication about what’s going on in Xinjiang. You also have this Australian research institute [Australian Strategic Policy Institute, ASPI—ed.] that continues to fabricate reports one after another about what’s going on in Xinjiang and elsewhere in China. We have a deliberate effort on the part of Washington and on the part of Western media to blacken China for no other purpose than to justify attacking and making everything negative, so that the American people are thoroughly, thoroughly brainwashed. It’s not possible for the American public to make a separate judgment. We don’t have any politicians of stature willing to come out and say, “Hey, we are going down the tubes if we continue on this path, because we’re going to come out lose-lose. Our economy is going to go in the tank. We’re not going to be benefiting from any collaboration, and we’re not going to solve any of the global problems like the pandemic, like climate change,” and so on and so forth.

So, I am very, very sad about where we are at this point. I applaud the Schiller Institute and Helga LaRouche and all the effort that you guys are doing, trying to get the message out. You probably have a better listenership in China and Russia and elsewhere. And somehow, we need to get your voice louder here in the United States.

Democracy for the People

EIR: Well, of course, their argument is that America is good, and China and Russia are bad because we are a “democracy” and they’re an “autocracy.” In fact, as you know, Biden just held the so-called Democracy Summit, trying to create an alliance of countries who are deemed by the U.S. to be “democratic” against those that are “authoritarian.” In fact, the question of what democracy is, is a very interesting and important discussion, and the Chinese have been talking about that. How would you describe democracy in the U.S. compared to democracy in China?

Dr. Koo: I think in the U.S., we are very flexible as to what democracy really is. If you’re a country on our side, you have democracy. If you’re against us, you have no democracy.

Now, what is the example of our democracy? Let me count the ways: Our democracy is where the two Parties bicker, nitpick, and get nothing done. We don’t look at the global issues, the bigger issues of what’s good for our country. We don’t move on infrastructure. We don’t invest in health care. We don’t really care much about education that we talk about. We care about who gets elected. We care about, how to maneuver the election mechanism so that the other side has a disadvantage and we have the advantage. We have people who violate the Constitution and the rule of law, and they’re still walking free, and we don’t seem to be able to do anything about it. These are some examples of democracy as we practice in America.

We also have democracy exercised in that if you live in the ghetto and if you’re Black, you don’t have a chance; you’re presumed guilty of everything we accuse you of, and it’s up to you to prove innocence. And that goes, by the way, for the Chinese-American scientists in this country. We can talk about that a little bit later. But democracy has become a very handy-dandy label, to blacken anybody that we don’t like and to pat ourselves on the back because we are supposed to be a democracy.

Now, I can’t explain fully what China means by democracy, but I do know that they respect the human life of every person in their country. They have spent a great amount of effort alleviating poverty for their remote poor, for the villagers who live in some of the worst situations and worst conditions. Admittedly, it may be a propaganda film, but I saw some films of Xi Jinping walking up these muddy trails to visit remote villages to find out how they’re living and how they’re doing. Do they have enough to eat? Do they have warm clothes to wear? Do they have enough blankets, and so on and so forth. He would hold little village conversations with the people and ask them what problems do they have and what issues do they have that they would like to bring up?

This is almost unheard of here. Here, when a politician comes to visit and have a town hall meeting, they usually have their hand out because they’re looking for political donations. This whole country’s election is run on money, and if you’re not in a position to write a big check, your voice really doesn’t count. So, there’s a very different way of practicing and exercising democracy, and we’re just kidding ourselves in this country that we all have “one man, one vote” type of equality.

Russia and Sun Tsu

EIR: Before I ask you more about the persecution of the Chinese and Chinese-Americans, let me ask about President Biden. As I’m sure you know, at this moment, the crisis over Ukraine is extremely intense, and yet meetings have been set up between the U.S. and Putin and the representatives of Russia to attempt to deal with this crisis, to guarantee some security for Russia. In fact, it was announced today that Biden is going to talk to Putin tomorrow [Dec. 30]. He also has had several long discussions with Xi Jinping. Do you see this President as having the intent or the ability to try to override this extreme anti-Russia, anti-China hysteria within the press and the Congress, and even within his own administration?

Dr. Koo: I’m doubtful that he could, because the situation that Russia and the U.S. is in, didn’t happen overnight. The NATO organization, for example, has been pushing and pushing, collecting members eastward, if you will, from Western Europe to the neighboring countries of Russia. And of course, this threatens Russia and Putin. And finally, Putin had to do something that will catch the attention of the West.

The way he did that—I learned this from one of the analysts from China—is really in accordance with Sun Tzu’s Art of War. You negotiate from power and from strength. By amassing Russian troops on the border of Ukraine, it’s sending a very unequivocal message, which is that if we don’t get the reasonable settlement of cease-and-desist of the encroachment by the West, we have the upper hand. We can go in and take the eastern Ukraine at will, and there’s nothing you can do about it. And that’s the fact. I think that’s what the Pentagon realizes and understands.

Whether Biden can effectively settle anything remains to be seen, because what Putin really wants, he’s made it very clear—he basically says, “Hey NATO, you need to sign a document that says you will cease and desist and not continue to expand your sphere of influence.” I think maybe some of the EU countries would be willing to go along, but NATO obviously is controlled by the U.S., and whether that’s going to happen remains to be seen.

FBI Witch-Hunt Against Chinese in America

EIR: It’s very dangerous.

So, on the persecution, you know that we’ve been very involved in documenting and opposing the effort by the Department of Justice and the FBI—starting actually a long time ago, but especially under Christopher Wray and the Trump administration and continuing today, with Wray still Director of the FBI—basically accusing anybody who is Chinese working in America, or Chinese-Americans who have any contact with China, are thereby automatically suspected of being spies. There have been some atrocious operations attacking leading scientists, who were helping to solve cancer and other diseases, who have been accused of spying, lost their jobs, lost their laboratories, and so forth. I know you’ve been an outspoken opponent of this, so I’d like you to say what you think needs to be said about that whole crisis in America today.

Dr. Koo: Again, for Chinese-Americans or ethnic Chinese and to some extent, Asians—because our FBI and our government officials don’t always tell the difference between one Chinese and another Asian—so we’re all being tarred. The system of justice, as applied to us, is justice on its head. You are guilty until you prove you are innocent. It’s very, very difficult to prove a negative, as we all know. When a federal prosecutor comes after you, they have infinite resources in supporting them. You can be driven to poverty from the mounting legal defense bills. Frequently, the hapless Chinese scientists basically have to cop a plea just to get out from under the pressure and get out from the financial ruin that they face.

This actually goes all the way back to J. Edgar Hoover. The bias against Chinese started from him. We had a “Chinese expert,” Paul Moore, not long retired now from the FBI, who basically said, if you see three Chinese at a cocktail party, they’re probably talking about the espionage and the intelligence that they’ve gathered. Just any three Chinese, or maybe Asians, could be guilty of spying. This guy used to be the carpool buddy of Robert Hanssen. They used to go to work together. Robert Hanssen, if you don’t remember, or don’t know, was indeed the biggest double agent for the Soviet Union before he was finally caught and sent to jail. He [Moore] never smelled a rat sitting next to Robert Hanssen, but he could see three Chinese standing on the corner as spying for China.

Moore also promulgated the “grains of sand” theory of espionage. What is “grains of sand”? Well, we have hundreds of thousands of Chinese in this country, and they are loyal to China. They gather any little tidbits of information and they send it to Beijing. The implication is that there’s a supercomputer in the basement of some building in Beijing, cranking through all this little intelligence, through this computer, and out the other end comes the design of the multi-headed missile. That’s the kind of logic that we are facing from the FBI and the Department of Justice. There are even FBI agents that came right out and admitted in their testimony that they lied because they had to fill their quota of cases against Chinese-Americans.

I think the long-term implication of this kind of bias is that we are going to lose. And the reason is, because the greatest source of STEM—science, technology, engineering, and math—graduates are coming from China. It’s proven through history that they have made tremendous contributions to American technology, American science, and also as American professors and teachers raising the next generation of students. So we are cutting our own nose to spite our face, because we are discouraging them from coming.

And they are indeed not as enthusiastic about coming to the U.S. More and more of them—I saw as many as 80% of the Chinese students who come in and graduate are now going back to China, because it’s just too damn risky for them to stay here and work here.

The Belt and Road in America

EIR: And all the time, the U.S. also is criticizing China for going out to the rest of the world with their development policy, what they learned in transforming their own country from poverty to one of the greatest economies in history. They are taking that to the rest of the world through the Belt and Road Initiative, which you’ve praised often, for trying to convey to other poor countries that the trick to getting out of poverty is building infrastructure and actually creating the conditions for a modern industrial country. You can only think that the attacks on the Belt and Road are coming from those who want to keep the world poor and divided and to keep China down.

Dr. Koo: Right.

EIR: Here in the U.S., our infrastructure is a disaster. We just passed a small infrastructure bill, which will barely dent the deficit we have. What can we do to get the U.S. to accept Chinese investment in U.S. infrastructure, which they wanted to do before this hysteria began? And even more important, how can we get the U.S. to recognize that it’s in its own interest to work with China on developing the real physical economies of nations in Africa and Asia and South America?

Dr. Koo: I think, Mike, you made an important summary statement, which is, what can we do to convince the American people it’s in our interest to work with China? There are plenty of examples of the benefit that can accrue.

For example, the Hamilton Bridge, which is the extension of the George Washington Bridge that goes over the Harlem River. That bridge was refurbished and rebuilt by a Chinese construction company that was based in New Jersey. That came within budget and on time. It employed American workers. Some of the management came from the China side, but the workers, the employment was good employment for the American workers. And that happened a few years ago. I wrote about it maybe two years ago.

Another example? The subway cars in Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles are being replaced by Chinese subway cars. These are coming from China, partially in kits, and are assembled in the U.S. The U.S. plant, I think, is outside Springfield, Massachusetts, and there may be another one being built outside of Chicago. The idea was, the state-of-the-art design and the siding and some of the important keys are being provided by China. But the inside air-conditioning, some of the other units, and so on are being provided locally, sourced in the U.S. The content of these cars is about 60% local content, meaning U.S. content, or more than 60%. So, it does qualify, according to the rules of satisfying being made locally.

It’s a win-win situation, because these subway cars are state-of-the art. They’re quieter, they’re safer, and they’re more economical. Their prices are lower than third-party sources. In point of fact, in the United States, we no longer have the capability of making these subway cars, so we have to outsource. The other outsources are more expensive than the Chinese source.

When the first car was delivered in Boston, there was a big hullabaloo, a source of celebration. The next targets the Chinese were looking at were New York and Washington. Then the politicians got into the act, and they said, “No, no, no, we can’t do that, because the Chinese could put in all these listening bugs in the subway car and spy on us while the cars are rolling into work.” Can you imagine you and I having a conversation? “Hey, Mike, how are the Yankees doing? You know, do you think they’re going to win the pennant this year?” And that goes to Beijing as espionage? How about that?

The Common Good

EIR: I think one of the primary issues which exemplifie why the world has to work together, is the out-of-control pandemic, this COVID pandemic. As I think you probably know, Helga Zepp-LaRouche and former U.S. Surgeon General in the United States, Dr. Joycelyn Elders, have formed something they call the Committee for the Coincidence of Opposites, an idea taken from the 15th-Century genius Nicholas of Cusa, who was largely responsible for the Renaissance in Europe. Cusa said that to overcome conflicts between religions or ethnicities or nations, you have to think of the higher principle of the common needs and desires of mankind as a whole.

This pandemic cannot be cured unless it’s cured everywhere, as we’ve seen by these variants coming back to bite us, because we refuse to build modern health care delivery systems in most countries and we’ve even hoarded vaccines from Africa and elsewhere.

Zepp-LaRouche and Dr. Elders are calling for is that we must build a modern health system in every country in the world, which would include not just the hospitals and doctors, but clean water and electricity, of which many countries have none. This is certainly the kind of aim that the Belt and Road Initiative is targeting. Do you think this health issue is a means whereby we can overcome this division and geopolitics and get the world to come together for the common aims of mankind?

Dr. Koo: Whether we get to the point you just summarized, will require a significant change in attitude in the United States. In China, people seem to naturally understand what’s for the greater good is more important than my individual druthers, my individual “exercise of freedom.” But that’s not the case here in the U.S. We even have people who object to vaccination because it’s an infringement on their personal freedom. If we have the inability to recognize what is the greater good in our own country, we will have even greater difficulty recognizing what is the greater good in solving the problem on a worldwide, global basis.

We’re lucky in the sense that we are richly endowed in water compared to many other places in the world. Therefore, it’s hard for us to appreciate the importance of water elsewhere, whether it’s in Africa or Asia or elsewhere. We are so concerned and care about where we come down on these issues, we don’t even think about the fact that these issues affect all of us and not just in our little circle, our little world of the United States. So, I think the task ahead is a monumental one for the organization, unfortunately.

Confucius in America

EIR: Maybe we should look back to Ben Franklin, who, as you probably know, was a great admirer of Confucius and the meritocracy system in China, and wanted to bring this idea of the common good—or the general welfare, as our Constitution calls it—into the U.S., in building the United States. But as you said, this has been lost in the process of so-called libertarian individual freedom.

Dr. Koo: Right. It’s way overdone.

EIR: Do you think we can teach Confucius to the American people?

Dr. Koo: Well, we’re throwing them out. You know, these Confucius Institutes are being thrown out rather than being welcomed at this point. And again, they’re being victimized by the biases that we have here. I mean, we have this Senator from Arkansas [Sen. Tom Cotton—ed.] who says, “Hey, we can’t let the Chinese in unless they want to come to study Shakespeare.” And I added, well, they could go to Oxford and Cambridge to study Shakespeare, not come to the University of Arkansas. Maybe they can study how to be a top football team in the AP poll in Arkansas.

EIR: Are there other issues you’d like to address to our audience and to the readers of EIR?

Dr. Koo: Well, Mike, it’s really nice having this conversation. I just feel so disappointed on the path the United States is taking at this point. We seem to be insatiable in wanting to pick fights. We seem to need a common adversary to justify our military budgets. There is only one issue that has overwhelming bipartisan support in this country, and that is increasing the military budget.

You have to ask, the American people need to ask: Why do we need an increased military budget? We can blow the world apart many times over with what we’ve got. What’s the point of intimidating everybody else? By intimidation, we think that we have other countries on our side. Actually, most countries fear us but do not like us, and do not admire what we’re doing.

That’s why I’m so glad we’re having this conversation. I just wish that we can help turn some people around, and encourage not just thought leaders, but politicians, to understand what’s at stake and start to speak out on what would be sensible and in the interests of our country.

EIR: Thank you very much; I appreciate this discussion. I think it should have ramifications throughout our country and hopefully around the world, that we can change America. I thank you again for doing our interview.

Dr. Koo: It’s been a pleasure. Mike, thank you for inviting me.

The following is an edited transcription of an interview with Russia expert Jens Jørgen Nielsen, by Michelle Rasmussen, Vice President of the Schiller Institute in Demark, conducted December 30, 2021. Mr. Nielsen has degrees in the history of ideas and communication. He is a former Moscow correspondent for the major Danish daily Politiken in the late 1990s. He is the author of several books about Russia and the Ukraine, and a leader of the Russian-Danish Dialogue organization. In addition, he is an associate professor of communication and cultural differences at the Niels Brock Business College in Denmark. Subheads have been added.

MR: Hello, viewers. I am Michelle Rasmussen, the Vice President of the Schiller Institute in Denmark. This is an interview with Jens Jørgen Nielsen from Denmark.

The Schiller Institute released a memorandum December 24 titled “Are We Sleepwalking into Thermonuclear World War III.” In the beginning, it states, “Ukraine is being used by geopolitical forces in the West that answer to the bankrupt speculative financial system, as the flashpoint to trigger a strategic showdown with Russia, a showdown which is already more dangerous than the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, and which could easily end up in a thermonuclear war which no one would win, and none would survive.”

Jens Jørgen, in the past days, Russian President Putin and other high-level spokesmen have stated that Russia’s red lines are about to be crossed, and they have called for treaty negotiations to come back from the brink. What are these red lines and how dangerous is the current situation?

Russian ‘Red Lines’

Prof. Nielsen: Thank you for inviting me. First, I would like to say that I think that the question you have raised here about red lines, and the question also about are we sleepwalking into a new war, is very relevant. Because, as an historian, I know what happened in 1914, at the beginning of the First World War—a kind of sleepwalking. No one really wanted the war, actually, but it ended up with war, and tens of million people were killed, and then the whole world disappeared at this time, and the world has never been the same. So, I think it’s a very, very relevant question that you are asking here.